Inheritance of Media Art

In June 2008, the World Heritage Committee has announced its decision to add the Hidden Christian Sites in the Nagasaki Region to the UNESCO’s World Heritage List. There are 12 sites including Oura Cathedral and the remains of Hara Castle as well as the villages of the hidden kirishitan (Hidden Christians) became the primary components for the recognition.

The Committee has applied the following criteria from 10 UNESCO defined criteria upon registration:

(ⅲ) To bear a unique or at least exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition or to a civilization which is living or which has disappeared.[1]

One thing to point out is that all of these 12 sites are testimonies that tell us the tradition of the hidden Christians who survived the period of prohibition that lasted over two centuries, from its formation to multiple transitions and ending. Additionally, the Japanese Agency for Cultural Affairs, in its World Heritage nomination document[2], has published its evaluation for authenticity by using the five attributes[3] assessing the efforts for sustaining the cultural background and uniqueness. Among the five attributes, which are “form and design,” “use and function,” “traditions, techniques and management systems,” “location and setting,” and “spirit and feeling,” the hidden Christians sites earned the highest points for “spirit and feeling.”

Previously, experts have claimed that sites that are preserved in its original state should be given priority in its nomination for the World Heritage as the inscription is only granted for tangible properties. However, during the “Nara Conference on Authenticity in Relation to the World Heritage Convention,” the members agreed that the inherited property should be considered and evaluated in the cultural context to which it belongs[4]. This decision has enabled disassembling (for repair) and restoration of cultural properties as long as their authenticity is secured.

These facts are highly suggestive in exploring ways to preserve or succeed media arts.

Authenticity and Integrity of Media Art

As most media art works use electronic devices that wear out in a relatively short time, therefore conservation of media art works in its initial condition is next to impossible. Also, some works involve audience participation or time-based media, offering the environment for a one-time only experience, similar to performing arts. The use of duplicatable/editable medium such as digital data or magnetic tapes suggests that different versions or derivatives can easily be produced. This means that “originality” in reference to uniqueness hardly applies to media art. Therefore, we must define the value of media art that replaces the concept of “originality” as well as its authenticity for evaluation. Such discussion may lead us further questions as to what identifies a media art work or what elements constitute an artwork.

On the other hand, integrity refers to the evaluation if an artwork embraces every element needed to maximize its universal value. The model that was developed by the Daniel Langlois Foundation in its DOCAM project[5] (Fig. 1) defines that integrity is a subordinate concept of authenticity, and consists of six components. They are:

Fig. 1. Source:Documentation and Conservation of the Media arts heritage: DOCAM(Last accessed in December 2013)http://www.docam.ca/en/about-cons.html

- Function

- Concept

- Material’s significance

- Work’s behavior

- Viewer’s experience

- Aesthetic

These attributes reveal an issue; “Concept,” “Material’s significance,” “Aesthetic,” and “Work’s behavior” rely on the technical and social backgrounds of the time that are constantly changing, and the cultural context to which media art belongs in terms of disciplinary is ambiguous. Even when the work still functions normally, it would be hard to translate the idea and innovation behind the work if it fails to convey the social significance and context of the time it was created.

Rooted in intermedia, computer arts, or video arts that were popular in 1950-60s, media art traditionally has evolved as a related field of art history. Catching up with the technological transitions along with seeking ways for survival covering multiple genres/contexts have made many media art works lose their places in the history as time passes. Even today, museum collections of time-based media works mostly consist of single-channel video or video installation, and technically complicated works such as media installation or internet-based art are rather rare compared to conventional form of art, suggesting that efforts to build foundation for understanding such types of art might have been lacking.

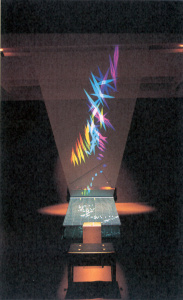

I would like to present a case in which a media art work was exhibited in a way that deteriorates its authenticity as a result of pursuing integrity incompletely even though the authenticity from the time of its origination was sustained. The following two photographs (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3) show how a signature work of Toshio Iwai Piano – as image media (1995) had been displayed in the museum. The work, whose idea was developed in 1990, is an interactive installation where the audience can play the piano and compose music with real-time generated sounds, just like they are drawing a picture. A computer-controlled piano was placed in the room with a screen extending from audience towards the instrument. Projected on the screen were scales and timeline in grid. The audience drew light dots on the grid, or the music score, as they interacted with the trackball. The light dots were flowing from the footsteps of the audience into the piano, triggering the keyboards to be activated. Simultaneously, an animation was generated to visualize the music being played, extending from the keyboard to the ceiling, which was projected on another screen that stood vertically from the piano.

The work was later on exhibited in Sasayama Children’s Museum. This time however, only one screen, which was originally extended from the footstep of the audience, was displayed. The trackball which served as the input interface had been replaced by a mouse. The screen was placed slightly away from the piano, and to comply with the rules of the venue, scaffolding was built in order to anchor the screen and the projector, taking the aesthetic details away from its original presentation.

(Left) Fig. 2. Exhibition view in galerie deux. (photographed in 1995. Iwai Toshio no shigoto to shuhen, Rikuyosha, 2000, Page 73)

(Right) Fig. 3. The work being exhibited in Sasayama Children’s Museum. (photographed in 2010. Courtesy of Sasayama Children’s Museum)

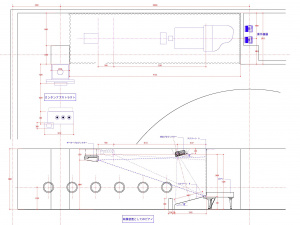

(Left) Fig. 4. The devices used in Sasayama Children’s Museum. (photographed in 2010. Courtesy of Sasayama Children’s Museum.)

(Right) Fig. 5. A part of blueprint drafted when the work was transferred from Nadya Park to Science Museum of Sea Life, Gamagori city. (Courtesy of Sasayama Children’s Museum.)

Piano – as image media was made in 1995 during a residency at ZKM. A performance piece was made in collaboration with Ryuichi Sakamoto as an expansion of this work, called Music Plays Images X Images Play Music (1996) and MPIXIPM (1997) and exhibited in Japan, and won the Golden Nica in the interactive art category at Prix Ars Electronica in 1997. Around the same time, Iwai also collaborated with Koichiro Eto to develop the work Remote Piano (1996) that played the piano remotely, and incorporated the performance into the work and made an installation. Similarly, the works that led up to Piano – as image media, such as Music Insects (1992), which was permanently exhibited at the Exploratorium (US), and Simtunes (1996), a game-based work, and the TENORI-ON (2007) developed together with Yamaha Corporation, which can be described as an additional expansion, cannot be neglected. Iwai materialized his core concepts of “drawing pictures and composing songs,”[6] and “the integration of music and moving image” through various works and game software, as if responding to the dynamic changes of digital technology during these times.

Piano – as image media was permanently exhibited at the Youth Center in Nadya Park (Aichi prefecture) from 1996 to 2004. It was then donated to the Science Museum of Sea Life, Gamagori city (Aichi) and it was renamed Odoroki Compose. Then it was moved to the Sasayama Children’s Museum (Hyogo prefecture) in 2010, and was exhibited until 2011, with the original computer surprisingly still functioning (Fig. 4)[7]. Currently, it is not exhibited since the designated manager changed. According to my research, conducted in 2010[8], the manager had never seen the piece in its original condition, and the only document available which shows the original work was a blueprint (Fig. 5).

This unique example exposed what would happen to a media art piece if the artist were absent, and if there was insufficient documentation about the piece. Obviously this is not how the artist intended for the piece to remain. However, as the majority of media art pieces created in the 1990s have disappeared through such natural selection-like processes, while the integrity of the work may be compromised, the process that Piano – as image media went through gives us clues for our examination of the inheritance of media art. There is significance in looking at the things that have been inherited despite the limited environments, and things that haven’t been inherited, and comparing them with other various examples and situations. Additionally, there is a need to think about the universal value of media art, where to build up its cultural context, by redefining the separation between the authenticity and integrity of media art.

The Last Resort to Conserve Media Art: A Reinterpretation

In the West, galleries and museums began discussing the conservation of video art and other time-based works that required audiovisual aids in the mid-1990s, prompting case studies and research on the subject. Thanks to over twenty years of various efforts, a basic course of action about media art conservation processes were established, and now they have moved on to discussions about human resource development and preparedness.

The four methods of media art conservation laid out in a report[9] by Variable Media Network, formed by the Guggenheim Museum (US) and the Daniel Langlois Foundation, are still considered the basic methodical approaches: Storage, Emulation, Migration, and Reinterpretation. These methods are combined according to the nature of each work when being implemented.

- Storage

This is the most conservative method, and refers to storage while the hardware is in maintenance to preserve its original condition, or when a part of it is being replaced with something of the same model. In the case of software, it is stored in a storage drive or computer without any changes. Additionally, often the deteriorated equipment is also preserved for its documentation value. - Emulation

This method replaces the functions of the hardware and software to a different platform, so that it works, using current variations of the technology required. Emulation is frequently implemented to replicate the OS, or the appearance, for games and computers. - Migration

This method refers to updating the various formats of hardware and software, and thus adapting it to a current or different environment. Should be differentiated with reformatting or copying. - Reinterpretation

Among the four methods, this technique “most radically intervenes with the integrity of the work.”[10] This is the last plan of action in the case that the technology used in the work has a special significance, and it is impossible to acquire the same apparatus, and furthermore, both emulation and migration are impossible. According to the Variable Media Network, “Reinterpretation is a dangerous technique when not warranted by the artist, (for the possibility of the concept being tampered with) but it may be the only way to re-create performance, installation, or networked art designed to vary with context.”[11]

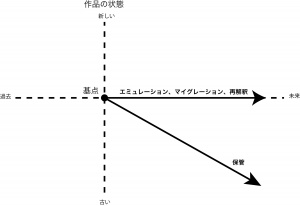

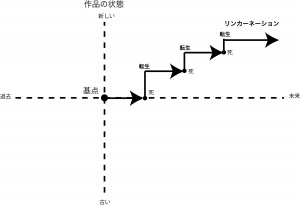

In this way, “Storage” is an effective means when the work is being preserved by anti-aging, or trying to revert its state to its original form. On the other hand, “Emulation,” “Migration”, and “Reinterpretation” prevents deterioration from the moment the work is finished, and aims to adapt to the times and technology through replication. In other words, they are methods that are effective in maintaining the condition. (Fig. 6)

Fig. 6. The Four Basic Strategies for Media Art Preservation (“Storage” “Emulation” “Migration” “Reinterpretation”) and the state of the work. (Made by the author, 2018)

Then under which conservation method would “reincarnation,”a fifth method presented in this exhibition, fit? In the sense of “rebirth,” works that have been restored or reproduced through “Emulation,” “Migration,” and “Reinterpretation,” that are different from the original condition but considered the same works, can be regarded as “rebirthed.” Furthermore, “reinterpretation” is a radical preservation strategy not only for its capacity in averting physical or technical deterioration, but for its aversion of becoming conceptually obsolete. If we somewhat forcibly hypothesize based on an extension of the “reinterpretation” method, “reincarnation” is not anti-aging or maintaining the status quo, but it can be considered a way to maintain the work’s innovativeness and preserve the work even as it develops it further (although at this point the word “preserve” may not even be appropriate). Additionally, while the aforementioned four basic strategies consider the state of the work when it is first created as the “complete” form of it, “reincarnation” considers the original form a point of departure, and takes the stand in maintaining the state of the work even as it lets the variability remain open to deliberation. (Fig. 7)

Figure 7. “Reincarnation” and the state of the work. (Made by the author, 2018)

For example, the artist Seiko Mikami states the reason for updating the version of the work in an interview[12] with myself in 2011:

For me, none of the works are completed to satisfaction, and it is always updated to move closer to the complete image in mind. Therefore, in regards to the differences in the versions, the latest one is closest to the final form of the work.[13]

When this interview was conducted, she was in the middle of recreating the work Molecular Informatics-morphogenic substance via eye tracking (1996), and in the process of thinking of a title. This work was premiered in 1996 at the Canon ARTLAB, and had gone through three version updates[14] since then. In the end, the work was remade at YCAM and titled Eye-Tracking Informatics. The title was changed, and it was not attached with “Version 5.0.” In that same interview, she told me that not only was the interface and technology modified, but it was changed into a work that focused on only the gaze, saying, “actually, it is becoming a different work from what it was.”

I imagine the debate on whether these two works, Molecular Informatics-morphogenic substance via eye tracking and Eye-Tracking Informatics are, in fact, the same work, would be split. When we consider that its concept, the base and core of the work, was inherited, but a new work was made through a process that differs from version updates, it presents itself as very close to the definition of “reincarnation.”

While the doubts about whether “reinterpretation” and “reincarnation” are possible in the absence of the artist still remain, this example is of interest for showing us, not the difficulty of succeeding the integrity of media art, but the reproduction of works can bear new creativities by the incomplete successions of the integrity of the work.

Incompleteness of Media Art

Kensuke Sembo, who is a member of the artist unit exonemo, is a co-curator and a participating artist of the “Reincarnation of Media Art.” In the opening talk, he referred media art in a positive way as “artworks that could die.” Nonetheless, the attempt for prolonging the life of media works which have a potential ending itself may be causing conflict and contradiction, both at the frontline of operation and through its practice.

Until now, museum-led efforts for the preservation of media art works have focused on life extension, so that works can continue to be displayed in public and inherit their value. However in this exhibition, the curators purposely added works and parts of works that otherwise require repair or that have stopped functioning properly as the samples of “death of media art,” to show the audience “incompleteness of art,” not only to show how works have lost their critical function but their evolving process or an intermediary point for unfinished works. And by creating the “Mausoleum of Media Art,” the exhibition unveils another value of imperfect media arts from both exhibitor and audience perspectives. Likewise, YCAM, whose exhibitions have been focused on commissioning new works, has offered new insight for revisiting the past media art works by paradoxically taking a conventional approach and holding this exhibition as a museum.

Further, the comments from the creator provided through the audio-visual guide, together with photographs, movies, printed matters, and other reference materials regarding the work, serve a key role in this exhibition filling the audience in on the background of the imperfect work. Of course art museums have placed importance on archiving the reference materials of media art works and projects, but this was for the sake of research and conservation, and the use of such archives for public viewing has never been the primary purpose. However in this exhibition, works and their archival material are treated equally as one, with works turning into archival material and vice-versa, telling the intention and the circumstance for each work. The audience then rediscovers the initial context from the work’s inception by picking up pieces of authenticity from the remaining works and archival materials. It may also be interesting to see how the device used for the audio guide impacts the level of rediscovery or the experience by audience.

Nostalgia for the past is perhaps the obstacle for inheriting innovation of media art. With its ambitious appraisal for (or rather finding a pleasure in) the works exhibited here as “imperfect,” this exhibition has marked a new epoch by eluding nostalgia and addressing the reinterpretation of media art which may inspire new creation.

[1] World Heritage Site terminology on the website of the Agency of Cultural Affairs:

http://www.bunka.go.jp/seisaku/bunkashingikai/bunkazai/sekaitokubetsu/01/sanko_2_3.html

(Accessed on June 19th, 2018) Other sites in which (ⅲ) was applied: Heijyokyo historical site, Stonehenge.

[2] “Hidden Christian Sites in the Nagasaki Region” Nomination document for world heritage registration, Agency of Cultural Affairs. 2017. P. 216.

[3] “Materials and substance” were added to certain parts of this.

[4] “Nara Document on Authenticity” November 1994. Article 11.

http://www.japan-icomos.org/charters/nara.pdf (Accessed on August 6th, 2018)

[5] DOCAM: Documentation and Conservation of the Media arts heritage(http://www.docam.ca/en.html) Implemented from 2004-2009.

[6] On his work shown in the exhibition, Toshio Iwai states in the audio guide that the work Sound Fantasy (1994) has its roots in his other work Music Insect (1992), and that the core concept is about “creating an image on the screen of the computer to compose music.” Additionally, he goes on to say that after Sound Fantasy, the “DNA” of the work was passed on to works such as Music Plays Images X Images Play Music (1996), and TENORI-ON (2007), the electric instrument created with Yamaha. Piano – as image media, which became the predecessor of Iwai’s performance piece with Ryuichi Sakamoto, can also be recognized as part of this process of the DNA inheritance.

[7] According to Iwai, of the computers shown in Figure 4., the Amiga4000 on top is an original from when the piece was made, and was used to project the video on the screen in the front and the trackball navigation, and control the piano. The computer on the bottom is not one of the original devices and its use is unknown. For the screen that goes up from the piano, an SGI computer (Silicon Graphics, Inc.) was originally used. It is possible that because this machine broke down, only the front screen was exhibited. (From an email to the author from Toshio Iwai, August 17th, 2018)

[8] “Documentation and Conservation of Media Art”

Research conducted as part of the Agency of Cultural Affair’s Media Arts Information Base/ Consortium Construction Project in 2010.

[9] Depocas, Alain. Ippolito, Jon. Jones, Caitlin. Eds. Performance Through Change: The Variable Media Approach. New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2003.

[10] Serexhe, Bernhard. Eds. Digital Art Conservation: Preservation of Digital Art: Theory and Practice. Vienna: AMBRA, 2013. P.601.

[11] http://www.variablemedia.net/e/welcome.html(accessed on August 7th, 2018)

[12] An English translation of the interview is included in the following publication:

Samuel Bianchini, Erik Verhagen, eds. Practicable: From Participation to Interaction in Contemporary Art. Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2016.

[13] Ibid. P. 671. *Here, the original Japanese is published.

[14] The first version update was conducted in September 1996, and the participant was increased from one person to two people. The second update was 1998, when a three dimensional audio system was employed. The third was 1999, when the vision detection quality was improved due to computer advancements. Additionally, a function was added so that the participant could influence the data of the past participant. (Reference: Seiko Mikami. About and around the “Molecular Informatics –Morphogenic Substance via Eye Tracking” Continuum. “Molecular Informatics –Morphogenic Substance via Eye Tracking” CEDMA, 2004. pp.7-38)